|

Article

published in French, in Format Cinéma No 47, Janvier 1986

|

Note

: when this was written, video equipment did not attain the quality it does

nowadays. |

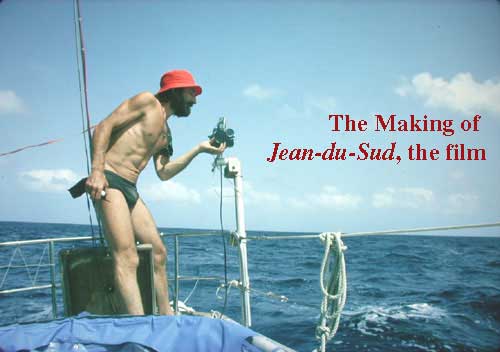

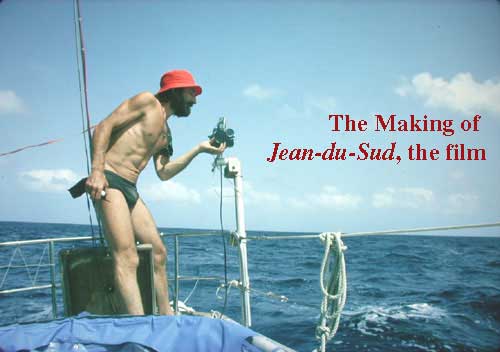

As soon as

I made the decision to work at preparing this single-handed non-stop voyage from

Saint-Malo, in France, to Gaspé, Québec, the other way around the world by way

of the Roaring Forties and Cape Horn, I also tried to find how I could share the

most intense moments with those I love.

It

happens that I grew up and spent 15 years of my professional career in the field

of the performing arts, first in theatre, then in television and finally cinema,

working as an actor, director, or production manager, often in more than one of

those functions simultaneously.

I

had had the pleasure of seeing Voyage au bout de la mer, the

unforgettable film that Bernard Moitessier brought back from his Long Way.

However, I had been left on my appetite : the sound track of the film was

made after he came back. I saw that in order to convey as faithfully as possible

what the single-hander experiences, it would be equally important to record

sound as to shoot images. If, other

than shooting subjective images like Moitessier, I spoke simply to a camera and

described the various events as if I was talking to a sailing buddy, I could

probably give the impression the viewers are sailing with me aboard Jean-du-Sud.

I wanted to make a film that I could project on a screen in a theatre, so

this ruled out using video equipment. I would shoot 16 mm film, with sync sound.

And I was sure there would be enough events during the voyage to hold the

viewer’s attention for an hour and a half, the normal duration of a

feature-length film.

I

believed, naïvely enough, that the funding I would find for the film would also

allow me to equip Jean-du-Sud for the voyage.

After a few months spent in Montréal trying to reach a production

agreement, I had to face reality : I would consider myself lucky if I raised

enough money to purchase some film and equipment.

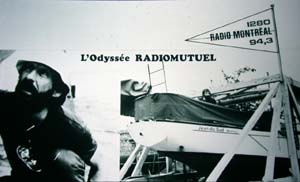

The

voyage itself had to be financed separately : in exchange for messages broadcast

daily from Jean-du-Sud, the Montréal radio station CKMF and other

stations of the Radio-Mutuel network provided what I needed to equip and

provision the boat. The

voyage itself had to be financed separately : in exchange for messages broadcast

daily from Jean-du-Sud, the Montréal radio station CKMF and other

stations of the Radio-Mutuel network provided what I needed to equip and

provision the boat.

From

the start, Robert Roy, responsible of external production and Philippe Lorrain,

responsible of film purchasing at the French network of Radio-Canada, favored

the project : Mr. Lorrain, a sailor himself, knew me as such and Mr. Roy knew me

as an actor and filmmaker. I do not

remember which one of the two said that if a Quebecer attempted such an

adventure, he should be encouraged and given the benefit of the doubt.

The

most difficult was finding a producer who would stake his reputation and

financial responsibility in such a risky venture.

Helped by Yves Michon, I was able to convince Jacques Pettigrew into

engaging his production company. Before starting Ciné-Groupe, he had shot the

film Cap au Nord that narrated sailing through the North-West Passage

aboard the 35 ft cutter J.-E. Bernier II.

Thanks

to the obstinate support of Jean Roy, the National Film Board of Canada lent us

the film and sound equipment : two Arriflex 16 S cameras, one case of lenses,

one Nagra tape recorder and some microphones.

The Arriflex is a quite robust camera, but I saw right away that I could

not use it in heavy weather. Even

if I tried protecting it with plastic bags, its electric motor would not resist

very long to being doused with seawater. I

insisted with Ciné-Groupe and at the Cape of Good Hope rendezvous, they brought

a small, robust spring-driven Bell-Howell, that I could dare bring topside in

heavy weather. After this, I used

the Arriflex only for sync sound shots. Almost

all hand held shots were done with the Bell-Howell. Thanks

to the obstinate support of Jean Roy, the National Film Board of Canada lent us

the film and sound equipment : two Arriflex 16 S cameras, one case of lenses,

one Nagra tape recorder and some microphones.

The Arriflex is a quite robust camera, but I saw right away that I could

not use it in heavy weather. Even

if I tried protecting it with plastic bags, its electric motor would not resist

very long to being doused with seawater. I

insisted with Ciné-Groupe and at the Cape of Good Hope rendezvous, they brought

a small, robust spring-driven Bell-Howell, that I could dare bring topside in

heavy weather. After this, I used

the Arriflex only for sync sound shots. Almost

all hand held shots were done with the Bell-Howell.

For

shots with sync sound, the Arriflex could be fastened in different places on the

boat. In fact, I ended up using

only four positions, two topside and two below : at both ends of the cockpit and

at both ends of the cabin, on the same side.

I was afraid that repetition of the same angles would bring monotony, but

the different conditions of weather, sea, light or the subject itself were

different enough from a scene to the other to avoid any sense of déjà vu.

enough from a scene to the other to avoid any sense of déjà vu.

Camera

support for the first leg was quite crude : a piece of aluminum tubing fastened

to the stern pulpit or to a bulkhead, on which an other short tube was

articulated. To hold the camera, I

simply had a bolt welded to a vise-grip : the bolt was screwed into the base of

the camera, locked in position with a locking nut and the vise-grip would bite

the aluminum tube.

I

was trying to imagine a way of taking the camera out of the boat.

As I was walking in front of a shop that sold kites, I had an idea : I

went in and asked if a kite could be powerful enough to fly a small camera; the

owner showed me an american magazine about kites, in which an article about a

meeting of amateurs of aerial kite photography mentioned the name of Lucien

Gibeault, a photographer from Valleyfield, Québec.

I contacted him and it turned out that he had found at this meeting that

he was among the most experienced on the subject. He told me all he had learned and presented me with two

beautiful kites of his fabrication. I

already had the ideal camera for this : a small Kodak Cine-Magazine, weighing

only two pounds, which my father had purchased the year I was born for shooting

home movies.

I

had no film to waste : I left with only 17 hundred-foot reels, this all we could

afford. Furthermore, if I wanted to do a second take, I had to bring

the camera inside to reload, and re-do the framing from the start; consequently,

almost all the scenes in the first leg were done in a single shot.

I used 36 reels in total; once edited, Part One is 1800 ft, which makes

for a 2:1 ratio only.

Nearing

the Island of Madeira, I met an other yacht, which, contrary to me, was stopping

there and I was able to give him my first 6 exposed reels for mailing to Montréal

. Once processed, they reassured

the people at home who still doubted of my ability for shooting good footage

with synchronous sound, alone aboard a boat and proved there could a film after

all. Two rendezvous at the Cape of Good Hope and in Australia were organized to

exchange footage shot for fresh and shoot complementary scenes.

I

was setting up the jury mast, after being dismasted, when I had the idea of a

small helmet camera : I would have liked to shoot the scene, but I had my hands

full already; but if I had a small camera with a wide-angle lens, I could shoot

anything, even sail changes in heavy weather.

During

the first leg, I almost did not think about the film : I shot spontaneously,

when light was good and something worth sharing was happening.

As soon as the scene was in the can, I tried to forget about it and

re-discovered the film when I screened my footage after I had flown back from

the Chatham Islands, following the dismasting of Jean-du-Sud.

Normand

Allaire had already started working on cutting the film and I saw right away I

could trust him completely : he gave the film a structure both poetic and

dramatic, pushing friendship as far as joining me at the Chatham Islands to

shoot the last images of the refitting and the second departure of Jean-du-Sud.

Filming

this second leg was very different : I had edited Part One and become conscious

of the need not to repeat myself and further synthesize the essential of the

experience. I even took the trouble

of writing some scenes ahead of time, carefully choosing each word in an effort

to transmit as precisely as possible what I was going through, and then

delivering them to the camera.

This

time, I had much better equipment at my disposal : first a small camera mounted

on a helmet, protected from salt spray, with a 5.9 mm lens that gave it a very

wide field of view, with the added advantage of a depth of field from 18 inches

to infinity. With this camera on my

head, I could shoot whatever I wanted. I was even able to swim away from the

boat and climb to the masthead with the camera on my head.

I

had a waterproof bag made for the Bell-Howell, and a camera mount that allowed

me to come back to the same framing after I had reloaded the camera.

We also spent a lot of energy fabricating a gimbal mount stabilized by a

gyroscope that was supposed to keep the horizon almost stable, while the boat

was moving up and down in the foreground. But

the seas of the Roaring Forties were stronger than the inertia of the gyroscope

and I could not use the mount.

For

recording the sound, I used for this second leg a small Walkman Professional

cassette recorder made by Sony (WM-D6), with a small lapel microphone (ECM-16T,

also by Sony). Besides being high

fidelity and very compact, this recorder had a quartz motor that was practically

synchronous with the camera. My

film stock allowance was more generous and I shot more film, but not more than a

ratio of 4 : 1.

I

had judged that for flying a kite from the cockpit of Jean-du-Sud and

have a wind as strong as possible, it should come from forward of the beam (it

came from behind, I would need to fly the kite from the forward deck and

blanketed by the sails, it would never take off).

Consequently, I had decided from the start that I would play with my kite

on my way back, as I would be sailing up the Atlantic close-hauled in the

Southeast trades. The technique is

as follows : the kite is launched and about 50 meters of line are let out (if

the wind is light, a second kite is launched on the same line).

If the kite flies nicely, the next step can be considered; otherwise,

more line is let out. The camera is then attached; to ensure that it is pointing

in the right direction, it is oriented along the line, which points to the boat.

I

had overlooked the problem of triggering the camera and after experimenting with

various methods, I came up with the solution of a sheet of paper folded in the

shape of a fan, clipped around the line : pushed up by the wind, it came in

contact with a mechanism made with aluminum wire and rubber bands that triggered

the camera. I attenuated possible

jerks by accelerating camera speed to 76 frames/second.

When

I did the shooting, and then when I worked on the editing, I made an effort of

communicate as faithfully as possible what I was going through.

I have seen With Jean-du-Sud Around the World a few hundred times

since then, always with as much pleasure. The

magic of cinema revives this wonderful experience that changed my life.

I do not know what pleasure my film brings to other viewers, but I hope

that at least it does not belie those two verses of the song by Gilles Vigneault

from which I named by boat :

When

Jean-du-Sud narrated his voyages,

We had the impression we were his crew.

|